"Many thanks to Gabriele Betancourt for inviting me to say a few words

about the quest for equity in our profession.Over the 50 years since I was in college, I’ve witnessed a lot of change and that is my topic.

I came to astronomy through physics departments, where there were even fewer women than in astronomy departments. For example, I was the only woman in my year who majored in physics at Tufts, then 1 of only 4 women among the 100+ graduate students in the Johns Hopkins Physics Department.

I didn’t think too much about this at the time, partly because I didn’t expect barriers to becoming a scientist. In the 1960s and 70s, civil rights laws had made discrimination illegal, and second-wave feminism opened up a world of new opportunities. My parents had very high expectations, and as a kid, I dreamed of being the first woman astronaut, Supreme Court justice or U.S. president (60 years later, we’re still waiting on that one).

If I’d thought harder about why there were so few women in my classes, I might have said women weren’t very interested in physics and astronomy.

I was very naïve!

With hindsight, many people interested in physics, and good at it, dropped away for one reason or another—like Eileen Pollack, one of the first two women to major in physics at Yale, whom I met in 2010 when she was writing her wonderful book, “The Only Woman in the Room: Why Physics Is Still a Boys’ Club,” to explain why she became a writer instead of her lifelong dream: a theoretical physicist.

Back then I didn’t realize women could be driven away by an environment that was unwelcoming at best and hostile at worst.

I was usually one of the stronger students in my physics classes. Still, people suggested I would get ahead mainly because of advantages given to women. (How many of you have heard this kind of thing?) The same language persists today—people say that women, people of color, members of the LGBTQ+ community, and other outsiders have risen to leadership positions only because they are “DEI hires.”

Meanwhile, I often felt like a fish out of water, or at least a blue fish in a sea full of red fish. That’s why simply hearing the name of a women astronomer was enormously reassuring.

At AAS meetings like this one, I would notice the few other women, each like a prize, an encouragement, an unspoken sign that what I was trying to do wasn’t crazy. (Back then, there was never a line in the women’s bathroom. Now look at all the women here tonight!)

My friend Anne Kinney, in her hilarious after-dinner speech at the 1992 Women in Astronomy meeting in Baltimore, talked about Margaret Burbidge being elected President of the AAS, and how hugely meaningful that was for her, despite knowing little to nothing about her. Anne said, “The name Margaret Burbidge was the light at the end of a very long, dark tunnel for me… If I had never heard that name, I am not sure that I would be in the field today.” Instead, Anne went on to a brilliant career working on the Hubble Space Telescope and at NASA and the NSF.

At some point, I started to think about all the women—and other outsiders—who weren’t able to stick it out, who lacked the support or resources that I had. I was, like Anne, so thirsty for role models. Weren’t we all? Far from having an easier path, we were running a tough race while handicapped with extra-heavy weights.

One particular conversation when I was a postdoc in the 1980s typified both the ubiquity and inaccuracy of the upside-down notion that women had it easier than men. It started with the usual statement from a male colleague that, thanks to affirmative action, I would have no difficulty advancing in the field (a claim wildly contrary to my experience to that point). I challenged him to substantiate that view. He launched into a story about a woman hired as faculty at a top university despite her weak qualifications, and despite overwhelming competition from an outstanding young man for whom the job had actually been intended. But an interfering Dean had insisted that this woman be added to the short list and then insisted that she be hired. I might have believed this story, but when I asked who the woman was and what her research area was, the storyteller didn’t know any details. Wait, I said, you don’t know who she is or what she does but you are sure she was unqualified? “Everyone knows this is true,” he responded.

As scientists, we know this isn’t how evidence and scientific analysis is supposed to work. Before coming to conclusions, we seek facts and are skeptical of broad claims—you don’t just accept some story because it aligns with your beliefs. Later, I happened to meet someone who had been on the actual search committee for that position. When I recounted the story to him, he—a person who was there, who participated in the deliberations and the decision to hire this woman—told me the story was flat out wrong. In fact, the woman had been on the short list from the get-go and was hired because she was the strongest candidate by far. According to this first-hand account, she blew the rest of them out of the water, including the young man who was a supposed shoo-in. (Maybe don’t repeat stories you can’t substantiate.)

This jolted me into a new awareness of the realities of my profession. I began to see that women were judged differently than men—indeed, much more harshly—which the social science literature confirms. (1998: Why So Slow? The Advancement of Women, by Virginia Valian, which summarizes a great deal of social science research.) Even today, women’s achievements are often discounted because of an assumed (nonexistent) advantage. (This book was a Eureka moment; it suddenly explained everything I had seen happening around me.)

Let me pause here to acknowledge that as a kid, I learned gender was binary; only later did I come to appreciate its fluidity and range. I am grateful to the friends and family and colleagues who enlightened me. Meanwhile, even though “women in astronomy” is too restrictive a frame, binary statistics do provide a handy metric for tracking change.

In 1987, I took a postdoc position at the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI), created in 1981. At that time, the tenure-track staff of 60 included only one woman (Neta Bahcall). This was despite the fact that women received 10-20% of the PhDs in astronomy in the 1980s. Three years later, I was the third woman hired onto the tenure track, after Anne Kinney. She and I started asking, “Why so few?” which prompted the Director, Riccardo Giacconi, to start asking his own questions, which led to STScI hiring Melissa McGrath, Stefi Baum, Laura Danly, Anuradha Koratkar, and many others, adding to amazing women on the operations staff, like Olivia Lupie, Vicki Balzano, and Pat Parker.

But better numbers were not enough. All the women at STScI were underpaid relative to the men. No matter how hard we worked, how many technical contributions we made, how many papers we wrote, how much grant money we brought in, we were not afforded the opportunities given our male counterparts, we were not nominated for internal or external recognition. Internally, we were less likely to be seen as academic stars, more likely to be criticized or overlooked. The discrimination was fairly blatant.

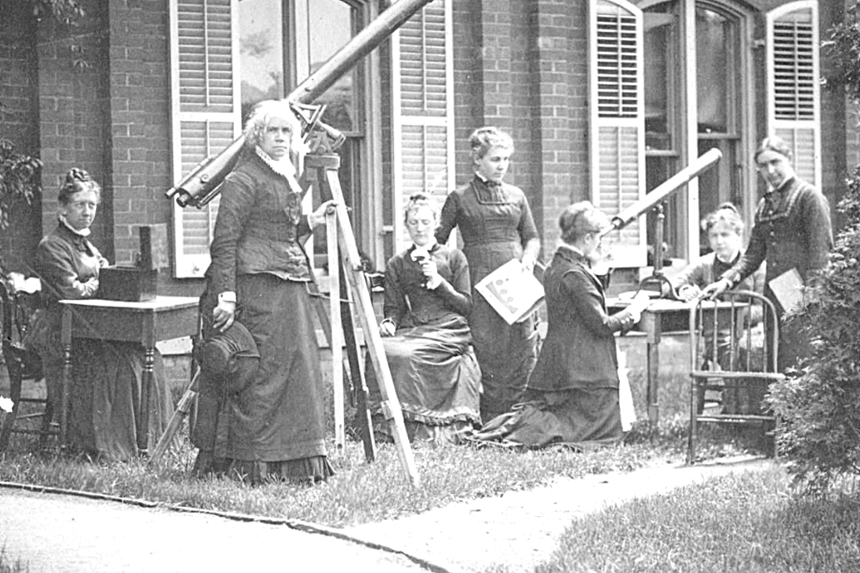

In response, the women banded together, at all levels—tenure-track, scientist track, research assistants, technical staff. We started having monthly lunches. At first, we mostly vented but eventually we dug into what was going on. We read about statistics, unconscious bias, stereotype threat. With the strong support of STScI management, we organized the first-ever conference for women in astronomy, in 1992. The registrations poured in and we quickly filled to capacity (limited by the size of the STScI auditorium). 150 of the 200 attendees were women. (Burbidge, Rubin, Wolff, Bahcall, Elmegreen, Humphreys, Mead, …)

None of us had ever been in the presence of so many women astronomers before. It induced in us a mental paradigm shift, analogous to how the famous 1968 Apollo 8 photo reframed humanity’s view of the Earth. We started to think differently about the lack of women on faculties, on speaker rosters, on lists of prize recipients. There wasn’t a dearth of talented women—they were simply under-recognized, not first to come to mind, ignored, passed over.

After the meeting, we turned conference discussions into the Baltimore Charter for Women in Astronomy. This brief manifesto stated the problem, recommended some simple improvements such as greater transparency and affirmative approaches, and called on everyone in the profession to be part of the solution. Despite the modesty of the Charter language, only a few institutions agreed to endorse it. I’m not sure why there was resistance. I am very grateful to Debbie Elmegreen, who persuaded the American Astronomical Society (AAS) to endorse the “goals of the Baltimore Charter” despite some opposition (including from women).

We had turned a corner. The focus was no longer, "What is the problem?" It was: Time to make change.

We went on the offensive, writing the Committee on the Status of Women in Astronomy’s newsletter STATUS and the AASWOMEN listserv, inviting experts to CSWA sessions at AAS meetings, putting forward names for women speakers at conferences, and nominating women for prizes. And things did begin to change faster. Networking among women and collective activism were the key.

Despite the 1992 meeting’s initial focus on women, we understood early on that the frame was far broader than gender. It was obvious that outsider status could follow from “gender, gender identity or expression, race, color, national or ethnic origin, religion or religious belief, age, marital status, sexual orientation, disabilities, veteran status,” and other reasons not related to scientific merit. The 2003 follow-on meeting in Pasadena explicitly addressed issues with regard to other minority groups, as did the third meeting in 2009, in College Park, Maryland. By the time of the Inclusive Astronomy meeting in Nashville in 2015, the commonalities and differences among these groups were regularly discussed, and broadening participation to all talent had become the theme.

From the 1990s to the 2000s to the present day, the number of women earning PhDs in astronomy increased steadily, from less than 20% to more than 40%. Interestingly, the percentage of astronomers who are women remains roughly double the percentage of physicists who are women, even though the two fields require the same knowledge base and skill set. The percentages also vary enormously from one country to the next. Across western Europe, where standards of living and levels of education are quite similar, the percentage of women in astronomy still varies widely. These facts indicate the participation of women is a cultural issue rather than a reflection of ability or interest.

Today, our field is far more sophisticated in its understanding of these issues. Most colleagues are familiar with the concepts of unconscious bias, of excellence following from inclusion rather than being in tension with it, and of the need for active intervention to rebalance the playing field. Indeed, I would claim that Astronomy has been a leader among the sciences. And though Chemistry and Biology graduate a higher percentage of women PhDs, Astronomy doesn’t have the fall-off-the-cliff profile of those fields after the postdoc years. We should be proud of what we as a community have accomplished—while still aspiring to do better.

|

| Inclusive Astronomy, Nashville, 2015. |

As the demographics in our field have changed, the culture has changed. To give just a few examples, in the past decade the AAS held Town Halls on sexual harassment in astronomy and racism in astronomy. These plenary discussions could never have happened at AAS meetings decades earlier, when mention of gender or discrimination was dismissed as a social issue not central to the business of astronomy.

I was particularly struck by Caitlin Casey’s Pierce Prize lecture at the January 2019 AAS meeting in Seattle, Washington, where she not only talked about her work on dust-obscured galaxies but also listed at the bottom of each slide some of the obstacles she encountered as a student and postdoc. Every single one of those was something I too had personally experienced decades earlier. But most importantly, her talk changed the conversation: at subsequent meetings, many talks—by men as well as women—have referenced career obstacles and hardships, in a way that builds community and inspires those coming up behind. This would not have happened had our field not changed in fundamental ways.

Young women still experience the same things that Caitlin Casey, I, and too many others have. But The Sky Is for Everyone. Change is slow and difficult. You have to keep pushing. At the January 2000 AAS meeting, I hosted a CSWA session centered around the 1999 MIT report on inequities among male and female faculty. One of the speakers, Prof. Claude Canizares (my former postdoctoral advisor), raised the question “When will we know we have succeeded?” His answer made perfect sense: when we reach parity. When a group attains representation in the inner sanctum in the same proportion as their presence in the talent pool, then you know the playing field is level. It’s a simple matter of justice that everyone have equal opportunity. But parity of experience between the dominant population and outsiders is still elusive. There is still work to be done.

How do we get to parity? I look to history for some lessons. First, we have to play the long game. Persistence is essential. It can be tempting, when one has right on one’s side, to think that simply making one good argument should be enough. It should be, but it rarely is. One has to make an argument over and over, to reset norms, often incrementally, and to be vigilant against the inevitable backlash. It’s like driving some electric cars: when you take your foot off the accelerator, it feels like hitting the brakes in a conventional car—you can't rely on momentum to carry you forward.

Another important lesson of history is whether we should preach or teach. By “preaching” I mean saying what you believe, in the language you personally resonate with, while “teaching” is saying what you want your students to learn, in language they will hear. For changing minds—especially those that aren’t inclined to change—teaching works better than preaching, even if preaching may be more satisfying in the moment. Think about your audience, try to motivate them by addressing what they care about. For example, in the context of equity, there are many different reasons to favor increased participation in science but for some audiences, excellence might be the argument that moves the needle.

History teaches us that the time scales for social change are long—often longer than a human life span. Women in the U.S. didn’t get the vote until 1920, more than 70 years after the 1848 Seneca Falls convention. And even now, some conservatives want to walk back women’s right to vote. The Equal Rights Amendment, which explicitly prohibits discrimination on the basis of sex, was introduced in 1923, re-introduced in 1971 and approved by supermajorities in both houses of Congress, but ratified by only 35 of the required 38 states. It probably wouldn’t pass Congress today.

Likewise, the battle to abolish slavery took centuries. Change is always harder and slower than it should be.

The struggle for justice is a lifelong effort. What each of us does will help, and no one thing we do will solve the problem right away. As the abolitionist minister Theodore Parker first said in 1853, and Martin Luther King rephrased, “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.”

Let me be very clear: I am not saying that it is okay that change takes so long. Rather, I am saying we need to be relentless, to make sure we complete that long arc toward justice.

My final suggestion: focus on a part of the problem you feel equipped to tackle. Maybe connect with one of the many organizations that work to get girls into science, engineering, computing, and mathematics. Work within your organization to ensure equity. Find a pressure point that works for you, keep your eye on the goal, and don’t stop until we get there."

Many thanks to Meg Urry for allowing us to publish these remarks, and for her presentation at the CSWA/1400 Degrees event January 5, 2026.